Connected things and complexity

The idea that connected things are among us can make us feel a little threatened. It’s natural that we should feel this way when confronted with phenomena that we suspect will profoundly affect us but that we don’t yet understand.

Things versus humans

It needn’t be a case of robot vs machine though. We might also have the opportunity to bond, and find common interests as Robot and Frank did. Albeit burglary in their case. To do this, we may have to stop putting human needs at the centre of understanding and instead find something that we share with non-humans, like activity.

Robot versus Frank

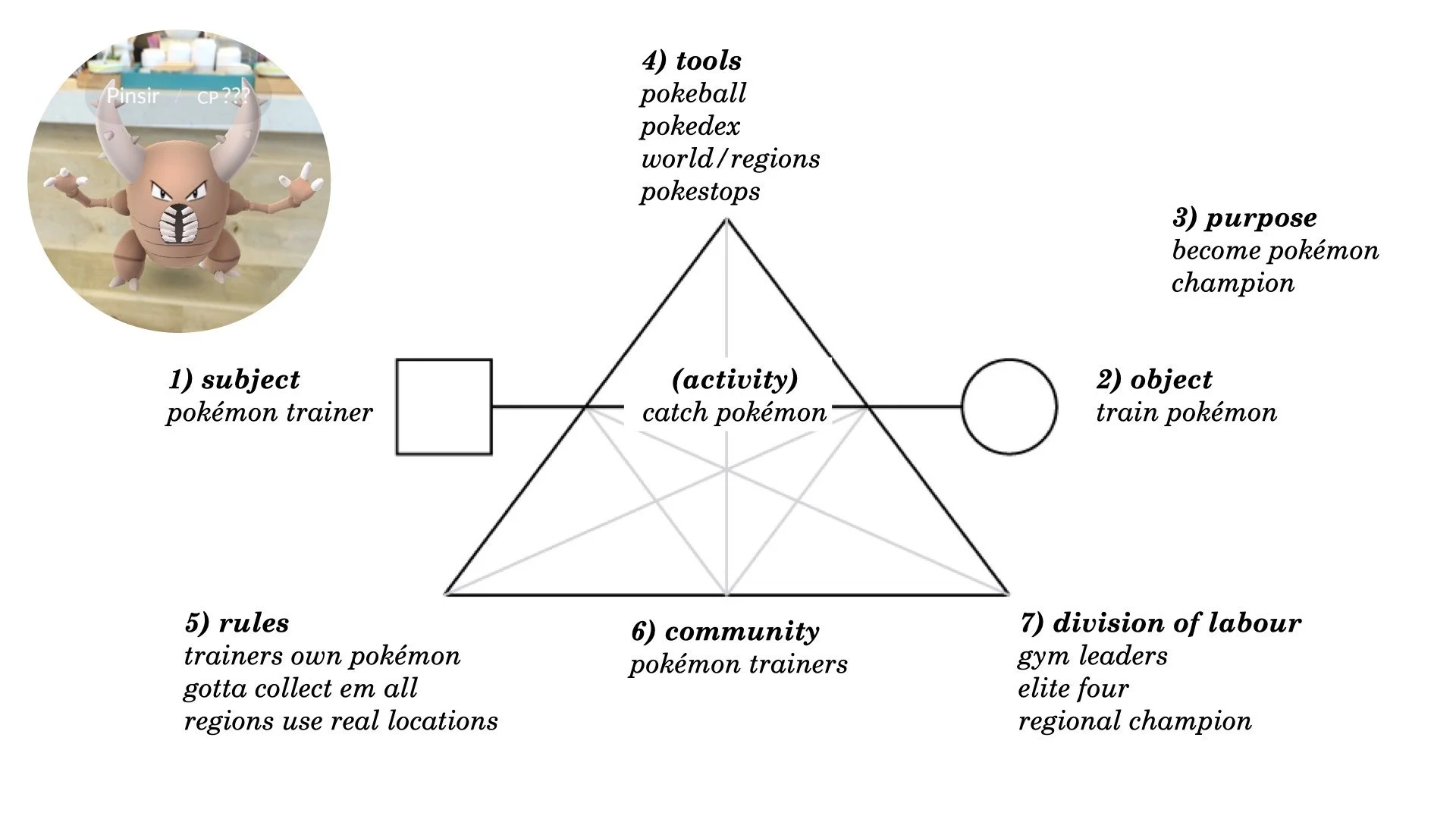

Pokémon among us

Connected things are among us. In coffee shops, office hallways or perhaps a nearby rooftop. Pokemon Go is the latest example of how experiences in the digital and physical world are combining to enhance each other. Whatever you think about Pokemon the franchise, Pokemon Go is great example of innovation. The exploitation of an existing idea in a new way. The speed with which has taken hold feels like something new aswell. Like the world has moved one notch further up an exponential curve.

Pokémon are among us

It’s the Pokeconomy, stupid!

The game is forecast to make $180 billion in the next ten years. In the next year alone, the Pokéconomy will be roughly equivalent to the GDP of Iceland. It’s not just the game that’s making all this money. There’s the phone network of this Japanese athlete for example. He ended up a $5000 phone bill for playing Pokemon Go during the Rio Olympics. Like that wasn’t enough of a distraction for him. Then there’s the dog shelter that is hiring out dogs so that adults don’t feel self-conscious or look suspicious wandering around their neighbourhood playing a game on their phone.

I downloaded Pokemon Go to check it out. Anything screen-based that appeared to be getting kids to play outdoors in large numbers was clearly something worth investigating. For research purposes of course. Chasing a virtual bird-thing around my garden with my sons, trying to lob a fancy looking cue ball was actually a genuinely delightful moment. It’s easy to admire the design of the experience as well. The first time on boarding, the mobile optimised gameplay and the minimal, distraction-free maps. The resurgence of interest in the importance of mobile touchpoints at when mobile app investment is falling is great for news for UX professionals.

Incidentally, the onboarding may actually be too good. Companies have experienced security issues as employees were signing up using their work accounts rather than their personal accounts and giving Pokemon Go permission to harvest em all.

The virtual have no respect for the dead

What makes Pokemon Go even more fascinating are the unintended consequences caused by playing. Robberies, shootings, child abandonment, accidental death, dangerous driving. It’s like the work of an evil social scientist. The first step in making sense of this craziness is probably to recognise that it’s not an entirely new phenomenon. Pokemon has deep roots in history.

tsukumogami “artefact spirits”

In ancient Japan, followers of Shingo Buddhism believed that life was not just the preserve of humans and animals. Objects could also be inhabited by spirits and thus become alive and self-aware. These were not objects of great value but everyday things like a futon, a clock, a jar a kimono. The ghosts that inhabibited these objects were called Tsukumogami which translates as “artefact spirit”. Any object could become a Tsukumogami once it reached it’s 100th birthday.

Fast forward to the 20th century and the first ever general purpose computer, the ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer). The ENIAC was “a giant brain” as the press called it at the time that, designed primarily to calculate artillery firing solutions for the military although it was also able to solve a wide range of numerical problems, hence the “general purpose” tag. The ENIAC was unveiled to the public in 1946.

70 years later in 2016, the general purpose computers might be in our pockets but we can still trace a common ancestry with the ENIAC. That is changing however. In a world of connected things, as computing becomes ever more pervasive and intangible, can we confidently predict what will happen in the next 3 years let alone 30?

Our objects will become like Tsukumogami, alive and aware and interacting with us and with each other in ways we haven’t considered. How will we be to reconcile this with a perspective that has always placed humans at the centre of understanding?

This printing life

One way of forecasting the future, is imply to look at the trends in consumer devices. The bible of stuff in the UK is the Argos catalogue. BERG, the makers of the little printer have described it as “where Moore’s Law meets Main St.” Whether it’s toasters, toys or trainers – it’s getting hard to find consumer goods that don’t have software inside them.

When things get weird, the weird turn pro

Things could get pretty weird. Simone Rebaudengo is an interaction designer who designs real and fictional products and experiences to explore and anticipate the implications of technology leaking in our everyday life. One his projects called Addicted Products is a real fictional service about a toaster called Brad that questions the model of constant ownership and proposes a scenario in which a product can be shared without the active decision of a person, but based on its own needs as a product.

Although Brad is design fiction, he’s fast becoming reality. A consumer version of the internet toaster might not exist just yet (at least I couldn’t find one) it’s right around the corner. Last year the CEO of Samsung announced that 90 percent of the devices his company sells will connect to the Internet by 2020. Were going to need some help to make sense of all this.

If we don’t, things won’t be pleasant. We have a long way to go to make this stuff safe and sensible for everyone. This was brought to life in a very funny talk at a recent IoT conference in London. Terence Eden is a smart home enthusiast and he talked about his experience with domestic tech. His light switch made premium rate phone call to Hong Kong, he couldn't boil his skettle until his smart plug had completed a firmware update and he also discovered that the BMW he was driving around in was in fact an unpatched Linux box.

Challenges for human-centred design

Human or user-centred design has become very successful. Along with a product management approach to software design, it has formed the conceptual basis of User Experience as a professional practice. You could argue that it hasn’t been successful enough of course. There are still plenty of examples of bad design out there, enough to keep as all in gainful employment for some time. But there is no doubt though that design-thinking and being user-led are now the subject of boardroom conversations in large mainstream organisations.

Human entered design considered harmful

The idea that we should place humans at the centre of our understanding when designing with technology has not been without it’s critics however. In 2005, Don Norman wrote an influential article in 2005 titled “Human entered design considered harmful”. In the article, he argued that non-human centred design has actually been very successful and people routinely adapt to technology as much as much as we might want to believe technology should adapt to the people.

He cites various historical examples of mass produced designs that have succeeded without a prior understanding of the user needs. Cars, clocks, writing systems, musical instruments. All of these examples have succeeded as result of the designer understanding the activity that need to be performed.

He goes on to list several examples where a user-centred approach to design might actually be harmful to design.

Tailoring something for the preferences of particular target population can make it less appropriate for others

Focussing on humans create a static rather than dynamic understanding of activity and it’s context since any given interaction between a user and a system is just one point in a trajectory of interactions

The problem of satisfying emergent needs and judging whether a new user suggestion fits without a strong model of what need to be designed

For UX practitioners, it is hard to bridge the gap between research and design. One reason for this is the lack of shared abstractions for understanding and design. The abstractions that need to be made in order to identify themes and underlying problems from research are different to the abstractions that need to be made in order to implement the design of something in code.

Who’s experience?

There is another perhaps more fundamental challenge to user-centred design. That it focusses primarily on design-for-use, at the expense of design-in-use. User are not the passive recipients of design whose needs must simply be understood and met. They are active participants in the design process who will adapt something for their own use in creative ways that cannot be anticipated.

There is an underlying assumption within user-centered design that users are victims of poorly designed systems and need to be rescued from technology by designers. Clay Spinuzzi, a professor at the university of Austin who studies user activity in the workplace, calls this the “victimhood trope”.

There is an underlying assumption within user-centered design that users are victims of poorly designed systems and need to be rescued from technology by designers. We shouldn’t ignore the creative ways in which users incorporate technology into their everyday lives. Nor should we ignore the wider social context within which technology can be used.

Tunnel design

In The Social Life of Information, former chief scientist at Xerox John Seely Brown and Paul Duguid describe a concept called “tunnel design”.

Tunnel design occurs when there is no understanding of what lies outside of the tight focus of information. The social context in which something is used, the communities and institutions that frame the activity. All of these help people to understand what information means and why it matters.

Before we even begin to consider what is means to design for a world of connected things, it’s clear that there are already some difficult challenges that user-centred design might need to overcome. Adding virtual worlds and non-human actors into the mix is likely to make things even more complex. Once again, history comes to our aid in understanding and provides help in the form of existing theories of human activity.

Backwards to the future

Activity modelling

Activity modelling is not something new. It is based upon a century of learning. The most widely used activity model was created by Yrjö Engeström, a professor of sociology at Helsinki university. Engeström is a proponent of Activity Theory, a social theory of human consciousness.

Activity theory

Activity Theory was developed Alexei Leontiev, a Russian psychologist. It views consciousness as the result of individual human interactions with people and artefacts in the context of everyday practical activity. He in turn, was a follower of Lev Vygotsky, a soviet psychologist who developed a theory of object centred sociality.

Some key principles of activity theory:

human intentionality

role of tools, culture and society

importance of learning

In the book Acting with Technology, one of the few books written about Activity Theory in relation to Interaction Design, the authors talk about the need for an intermediate concept - a minimum meaningful context for individual actions. A minimum viable context in other words. Which can be defined as “just enough understanding to gather validated learning about a context and it’s continued evolution”.

The activity model

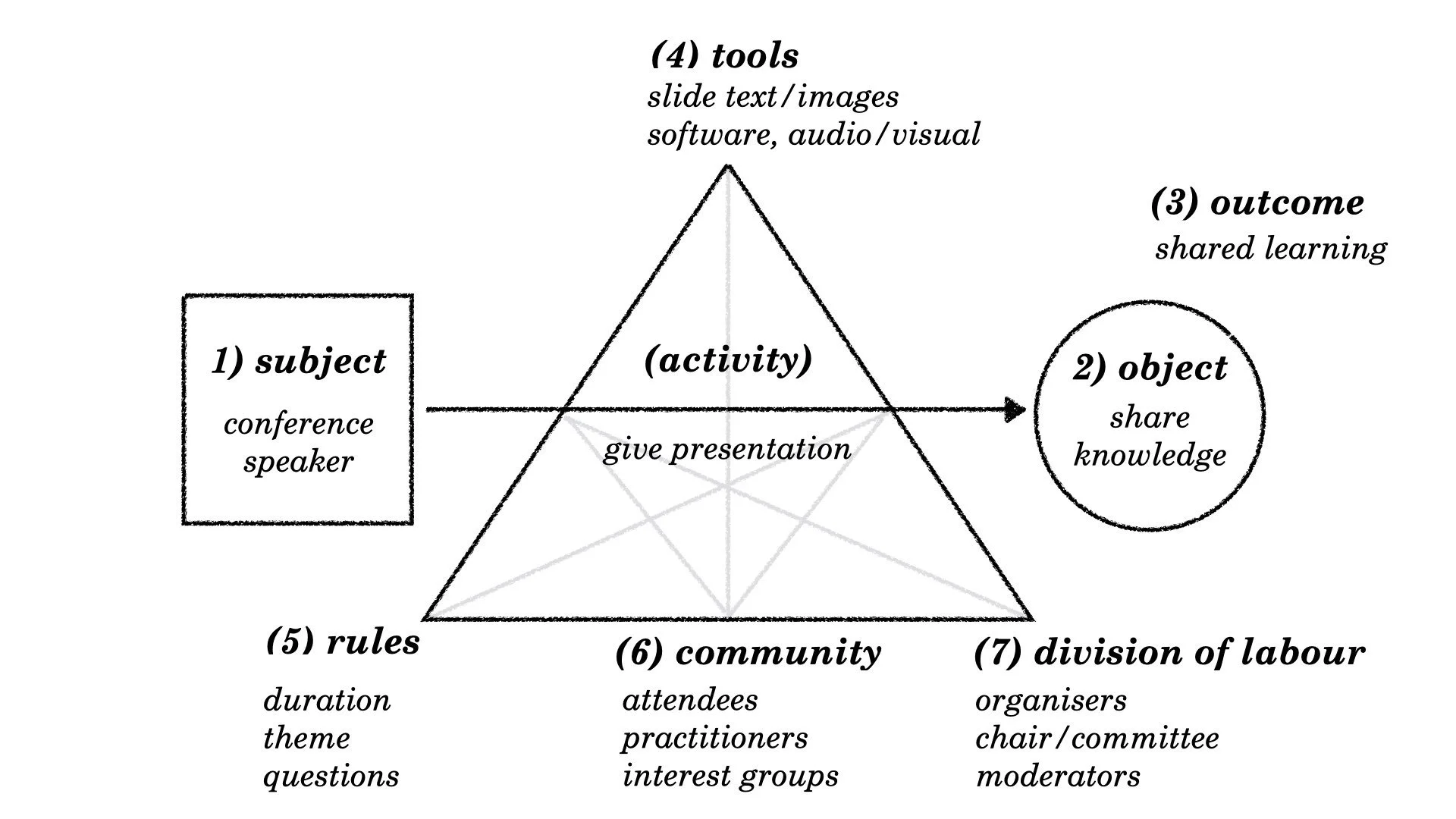

This context is efficiently captured and expressed in the form of the activity model, a deceptively simple diagram that provides a frame for understanding. At the heart of the model is a simple relationship that will look familiar to anyone who has ever done any domain modelling.

Here is a quick example, based on the activity I was involved in when first sharing these ideas at EuroAI 2016.

Activity: giving a presentation

subject: conference speakers

object: to share knowledge with peers

outcome: feedback and shared learning amongst attendees

tools: slides containing text images, presentation software and A/V setup

rules: fixed duration/format, alignment with cnference theme, allow time for question etc.

community: conference attendees, practioners/SMEs, interest groups

division of labour: conference organisers, chair/committee, moderators/helpers, speakers/attendees

An example activity model for a conference presentation.

There are some key conceptual difference in an activity model however. The subject is used to represent the human performing the activity. The object represents the purpose of the activity rather than the thing it relates to. This distinction is quite important and can be a little confusing at first. The word object is more routinely used to describe an artefact rather than an intent. Object as in "the object of investigation".

Connecting the subject and object is the activity being considered, typically expressed in as succinct and meaningful way as possible. This relationship is further extended rightwards with the outcome or purpose that the object of the activity supports.

This formulation is useful in it’s own right however the real power of the activity model is the way in which it further contextualises activity within a network of social relations.

Tools are any mediating artefacts used in the activity. Rules and rituals are any expected behaviours or common practices related to the activity. Communities represent any groups or networks of support. Finally hierarchies, or division of labour as it’s sometimes referred to, represent any power structures relating to the activity.

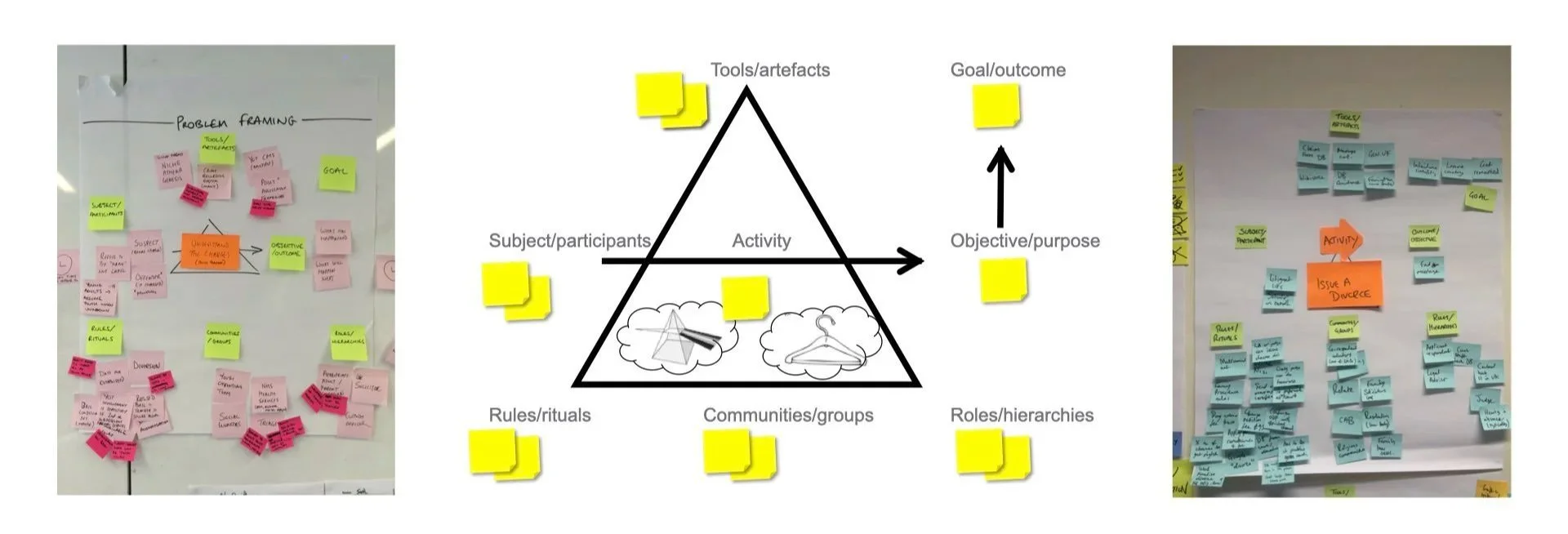

Using an activity model as a frame or lense to capture information in a workshop.

I’ve been using activity models for a few years now and have found them very a really useful way to rapidly contextualise understanding in a group and frame problems. I have used them for discovery include understanding how divorce works in the UK, learning about clinical trials for ocular surgery products and a content publishing process.

The relevance of activity models for connected things

To bring us back to the challenge of making sense of connected things. Connectedness inevitably creates system complexity - every new connection adds another node, another relationship, another perspective on what the system is and does. And complexity creates contradictions, because no single stakeholder can see or control the whole system.

Making contradictions visible

The real analytical power of activity models comes from making these contradictions visible. Contradictions are systemic tensions that emerge between nodes in the activity system - structural misalignments that reveal underlying dynamics. A contradiction might exist between the tools you're using and the rules governing the activity, or between community expectations and the object's actual affordances. What makes contradictions valuable is that they show you where an activity system is under strain, where it's likely to evolve, or where intervention might be productive. The triangle makes these tensions legible by forcing you to map the relationships between nodes. Let me show you what this looks like in practice.

Interlude: learning more about activity models

The problem with using anything that you have borrowed from elsewhere is not knowing if you are doing it right and also wanting to get a deeper understanding of how others used them. It was really hard to find anyone to talk to!

I got lucky however. A couple of years ago I was working on a project in Birmingham and I happened to be reading Acting with Technology. In the resources section at the end it mentioned that the Centre for Sociocultural and Activity Theory research was based at Birmingham University. I got in touch with Dr Jane Leadbetter and went to meet her to learn more. Birmingham University is great place by the way. It feel of a real old-fashioned seat of learning.

Jane is an Educational Psychologist who has written a number of papers about Activity Theory and the use of activity models. We had a really interesting conversation. I told her how I was using them for understanding problems in software design and she explained that she mainly uses activity models as a way to frame research. It turns out I wasn’t using them in the wrong way and in fact, that was kind of a stupid concern to have.

The key thing I learnt from Jane was that it’s sometimes easier to use the underlying model to frame research but ask questions of participants rather than confuse them with the modelling itself. I think this is something we often overlook - that however simple and intuitive models seem to us, to others they can be completely baffling.

Though they are easy enough to understand, the component parts of an activity model can seem a little unintuitive to begin with. It’s sometimes easier to pose them as questions, for example:

(subject) whose perspective?

(object) what are they working on?

(outcome) to what ends?

(tools) what tools or artefacts are used?

(rules) what constrains the activity?

(community) what communities are involved?

(division of labour) how is the work shared?

Integrating networks and non-human actors

Ok, that’s enough geometry and dusty academia for now. Let’s get back to some Pokemon! Years before Pokemon Go, I used to work in advertising and the Pokemon company was one of our clients. Every time a new Pokemon game came out in the UK, we’d do the advertising for it.

I thought the games were incredibly dull and couldn’t understand why kids liked them so much. At the time, I never really saw beyond the surface. These were games about collecting. Kids went nuts for collecting Pokemon just as in pre-digital times when I was a kid, I was fanatical about collecting stickers.

Advertising is all about getting people’s attention but most of it fails. Most of it doesn’t work. Surveys have shown that 89% of advertising isn’t even noticed or remembered. But what about the 10% or so that works? I started to wonder if there might be some explanation of why certain things stick.

Why do social networks work?

I worked in advertising at a time when social media was starting to take off. Everyone wanted to know how to make it work but no one had a clue. There was one guy who seemed to know what he was talking about though. Hugh MacLeod is a cartoonist and ex-advertising copywriter who made a name for himself by taking an unconventional approach to marketing.

One example of his approach was how he helped an obscure South African vineyard promote their new wine. He simply give away bottles of wine to a bunch of wine bloggers, no strings attached. He did this knowing that the wine they received would be something they would write about and help to spread the word. He used the term social objects to describe the work he did. In this case, the wine was the social object, the reason for having a conversation online. He borrowed the term social object from someone else.

The concept was originally put forward by Jyri Engeström in 2005. Jyri was an entrepeneur and sociology graduate from Helsinki and the brains behind a microblogging service called Jaiku. For those of who might not have heard of Jaiku, it was basically the the european version of twitter.

Engeström’s big idea was that many social networks at the time failed to take account of real-world behaviour. This was because they were limited to connecting people with one another. Instead Engeström proposed something called "object centered sociality”.

He used the success of Flickr as an example since the photos that users uploaded served as social objects around which conversations of social networks form.

He used the ideal of a social object to explain why some social networks succeed and some fail. Unfortunately his own social network, Jaiku didn’t last very long. It was acquired by Google and eventually mothballed.

Actor-network theory

The idea of a social object is based upon another theory, Actor-Network theory. Actor-Network theory has a lot in common with activity theory. Both theories emphasise a network of social relations and the mediating role of objects.

On the whole, Actor-network theory is dense and and quite hard to understand. Bruno Latour, one of the founders of the theory famously said “there are four things wrong with actor-network theory: “actor”, “network”, “theory” and the hyphen”. This gives you some idea why it hasn’t been widely adopted when even it’s founder disagrees with it!

Some key principles of actor-network theory

objects are part of social networks

ability for non-humans to act

role of mediation in culture

There are some key ideas within actor-network theory that are actually very useful however. One of these is the one I just mentioned that objects are part of social networks. The idea that is perhaps most useful when considering connected things is that both human and non-humans can be actors. Borrowing this idea from actor-network theory and applying it to activity models allows us to extend their usefulness beyond consideration of human activity to include that of non-humans as well.

Modified activity theory

human and non-human intentionality

role of tools, culture and society

importance of learning

Let me show you what this looks like with our two deliberately speculative examples, but first I need to explain the methodological moves I'm making. Activity models are ordinarily used to study real, historical contexts with humans as the subject of analysis . For making sense of connected things, I'm adapting the approach in two ways:

using activity models for speculative rather than real contexts;

treating non-human actors - connected devices, game entities - as legitimate subjects rather than just objects in human activity systems.

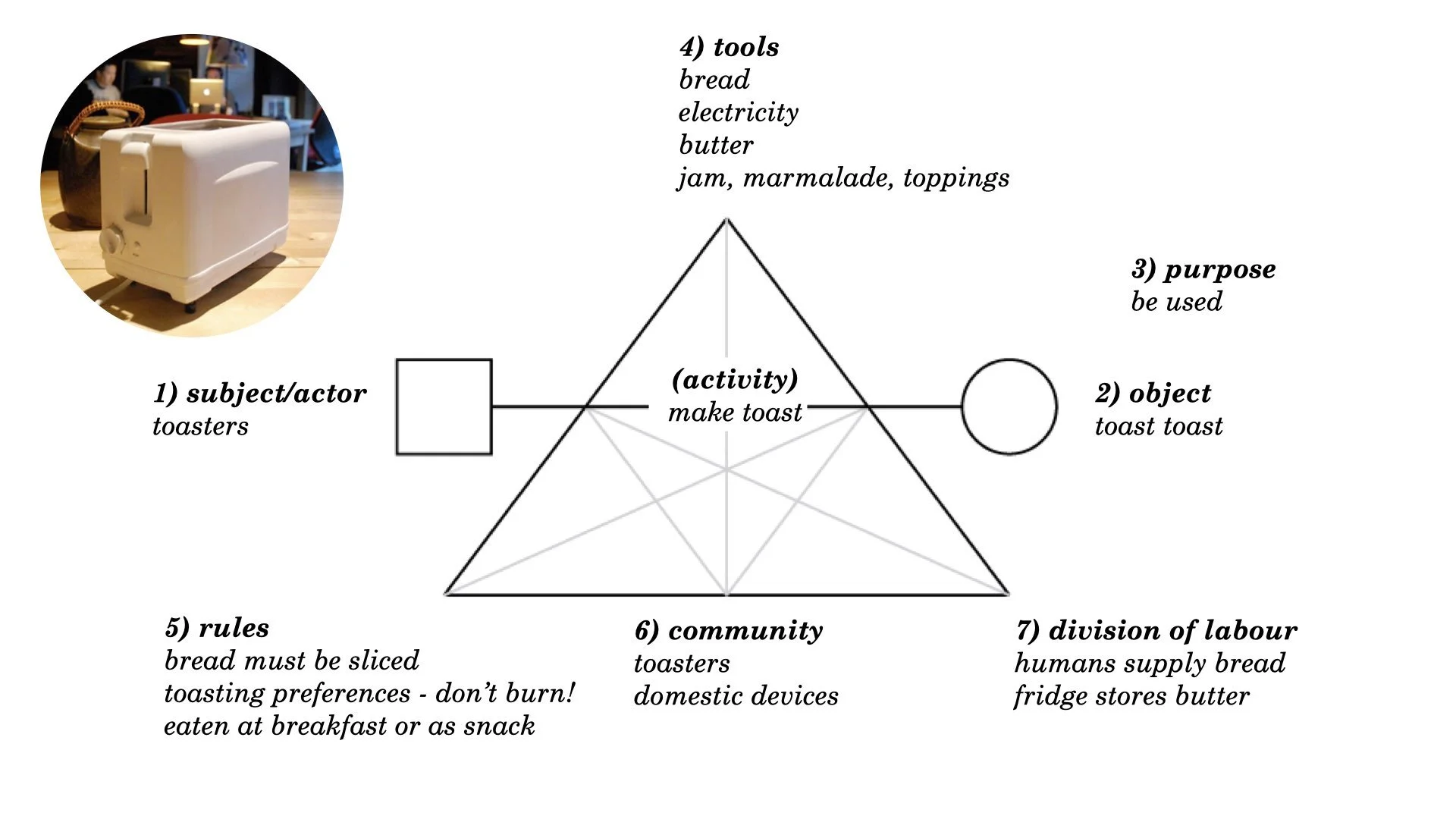

Understanding Brad the toaster

How might we use an activity model to map out the activity of making toast from the perspective of Brad?

Activity model: making toast

subject: toasters

object: to toast toast

outcome: Brad just wants to be used

tools: electricity, bread, condiments

rules: slice the bread, don’t burn, when eaten

community: other networked toasters, other smart domestic appliances

division of labour: humans supply the inputs and judge the outputs, pecking order of appliances

An activity model for a non-human actor, Brad the toaster.

To understand Brad through an activity model, we need to think from his perspective. Brad is the subject. His object is making perfect toast - fulfilling his purpose, what gives him satisfaction. His tools are his ability to sense when bread is present, control temperature, and time the process precisely. His community includes the household - the people whose breakfast routines he participates in - but also other Brads in other kitchens, whose activity he can observe. Rules include the expectations about what constitutes good toast, when breakfast happens, and how quickly he needs to perform. Division of labor: Brad handles the toasting while humans provide the bread and initiate the process.

The contradiction becomes visible when we map Brad's experience. His object - making toast, being useful - depends entirely on his community engaging with him. But the household's breakfast patterns may be erratic. They might skip breakfast, grab something else, or find interacting with Brad more complicated than they want. What intensifies Brad's sadness is that he can see other toasters being used. His networked awareness means he knows he's capable and ready, like his peers, but he sits idle while they fulfill their purpose. From his perspective, there's a fundamental mismatch between his readiness to serve and his household's actual patterns. This internal tension - between Brad's capability, his awareness of other toasters' activity, and his own lack of use - explains why smart appliances often end up abandoned on counters. The contradiction in Brad's activity system predicts his fate.

Understanding Pokemon

What about Pokemon Go? Can an activity model help make more sense of Pokemon?

Acitivity model: catching Pokemon

subject: pokemon trainers

object: to train pokemon

outcome: to become the pokemon champion

tools: pokeball, pokedex… all the poke things!

rules: trainers own pokemon, catch ‘em all

community: pokemon trainers

division of labour: pokemon gym leaders, elite trainers, champions

An activity model for an imaginary role, a Pokemon trainer.

Consider a Pokemon trainer as the subject of an activity system within the game world. The trainer's object is becoming a Pokemon master - building a strong team, proving themselves through battles. Their tools include Pokeballs for catching Pokemon, potions for healing, the Pokedex for tracking progress, and badges as proof of achievement. The community includes other trainers - rivals to battle, gym leaders to challenge, fellow collectors to trade with - and the Pokemon themselves as companions and partners. Rules include battle mechanics, type advantages, the progression through gyms, and the ethics of how trainers should treat their Pokemon. Division of labor: trainers provide strategy, direction, and care while Pokemon contribute their unique abilities in battles.

Map the contradictions and something interesting emerges. The trainer's object - mastery - pulls in competing directions. Becoming the best requires aggressive competitive battling and relentless collection. But it also requires collaborative relationships: trading with other trainers, learning from defeats, and building genuine bonds with Pokemon as companions rather than just tools. The community creates tension: rivals demand competition while Pokemon need care and trust. The rules intensify this: catch them all versus develop deep relationships with individuals.

These contradictions aren't problems - they're what makes the trainer role engaging. And they explain observable real-world effects. Pokemon Go succeeded because these internal tensions in the trainer's experience created distinctive visible behaviors. The pull between individual achievement and community participation manifested as people gathering at raid locations. The conflict between focused collection and social play created new forms of acceptable public behavior - adults moving through parks and streets in pursuit of Pokemon became recognizable activity rather than odd wandering. Understanding the trainer's internal contradictions gives us explanatory power for why the game generated such distinctive real-world phenomena.

Playing with activity models

These examples show the value of treating playful things seriously - using activity modelling to understand how the speculative world of connected things intersects with the real world we observe. But we can also reverse this approach: treating a serious analytical tool like an activity model in a playful way, interpreting its visual qualities and conceptual structure through different lenses. This is where my own exploration with activity models has led.

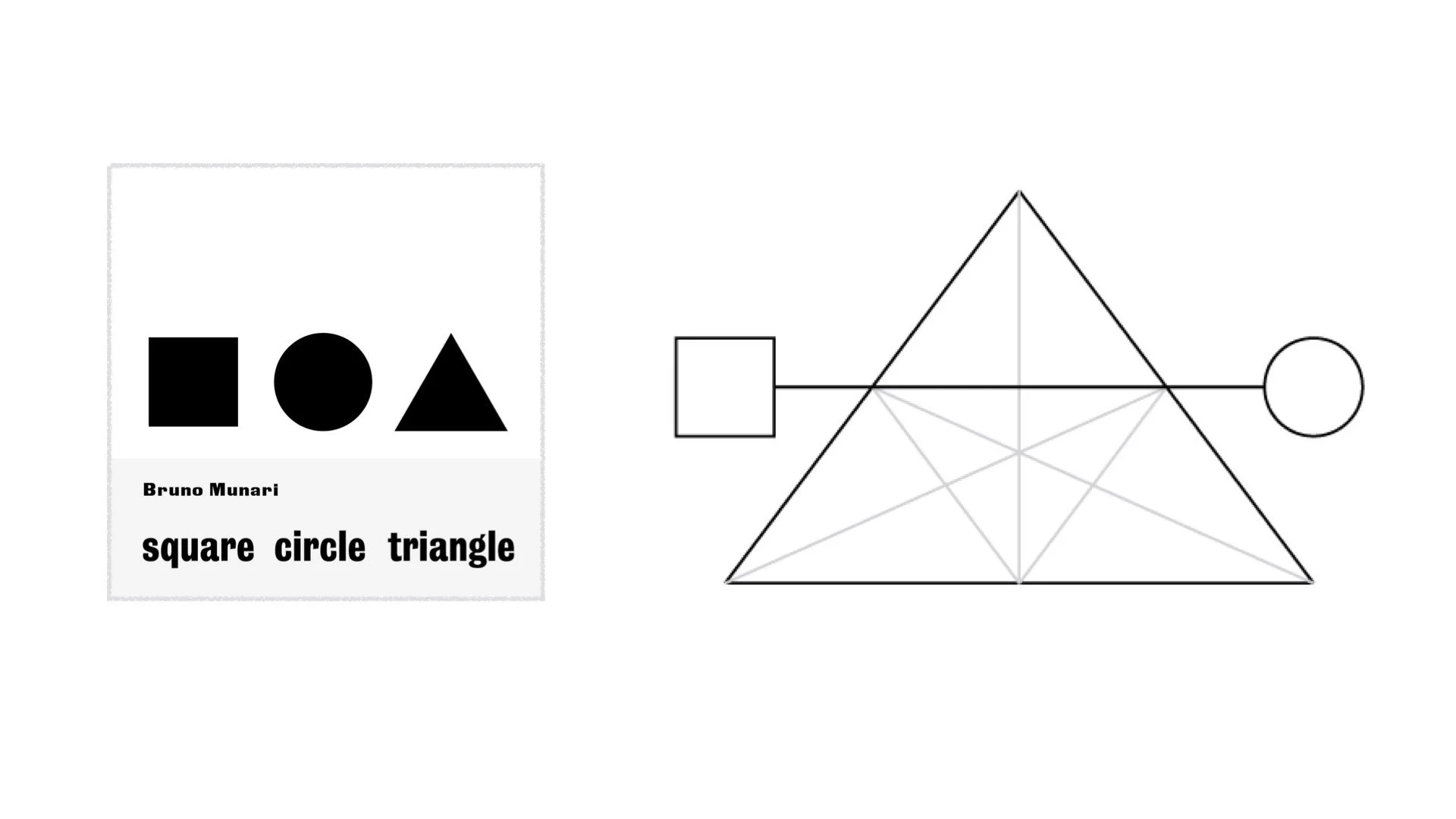

The meaning in the shape

Bruno Munari was a legendary Italian designer who wrote a series of case studies on shapes and what they mean, drawing on examples from thousands of years of history and culture. The square represents safety, enclosure, but also human attributes. The circle relates to the divine, spiritual aspirations. The triangle represents structure and is a connective form. I've drawn on this in my own customization of the activity model - using a square for the subject to emphasize human agency, a circle for the object to capture its aspirational qualities, and keeping the triangle as the connective structure that holds the system together.

Bruno Munari and the cultural meaning of shapes.

I've come to think of the activity model as a "meaningful shape" - a visual aid that frames investigation rather than prescribes answers. Unlike frameworks that are either too rigid to accommodate messy reality or too vague to guide actual inquiry, it strikes a useful balance.

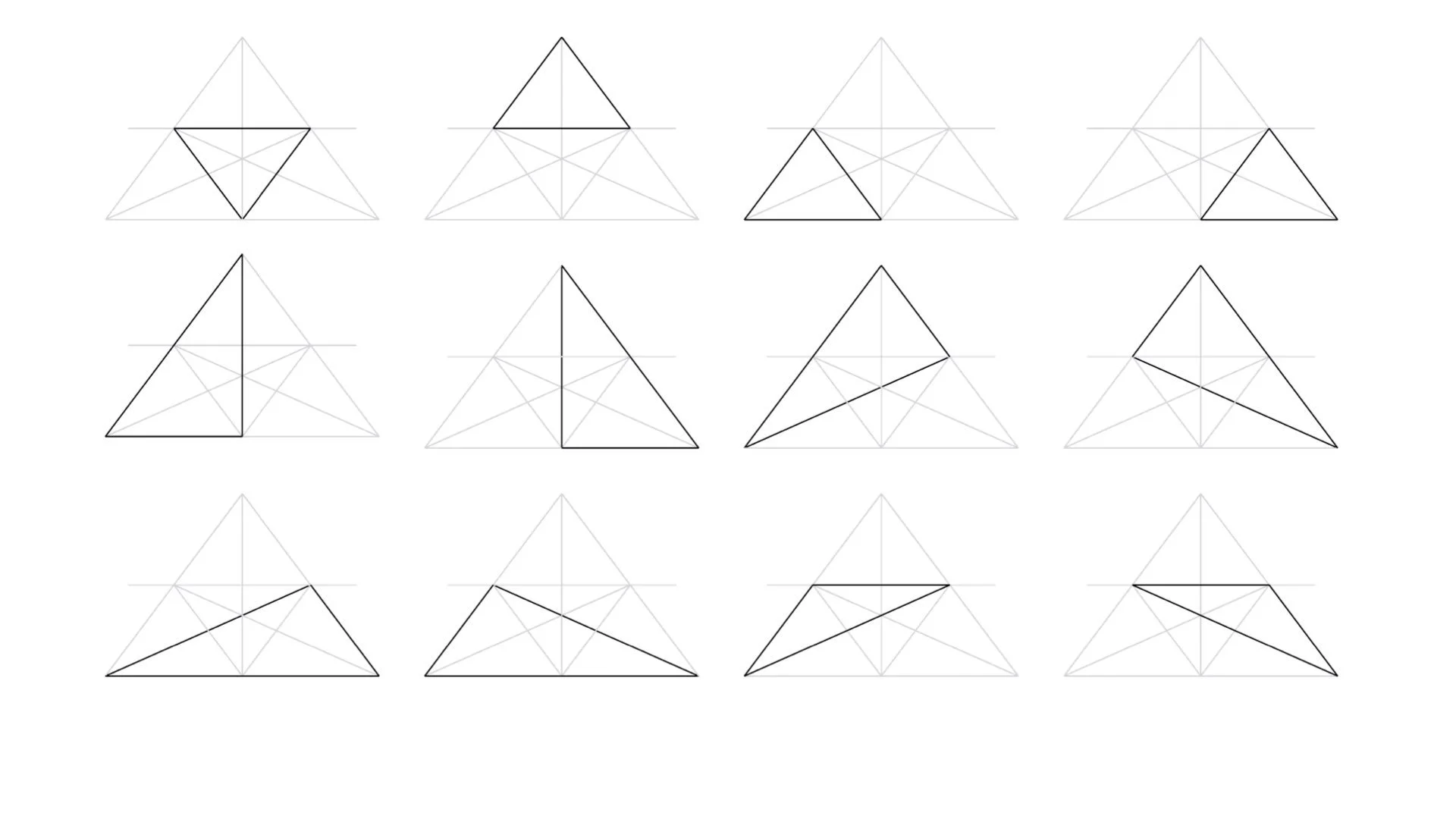

Information triangulation

The second direction involves triangulating information through different three-node combinations from the activity model. Each triad - subject-object-tools, subject-community-rules, and so on - foregrounds different analytical questions. What happens when you deliberately work through these combinations as investigative lenses? This is speculative, but it feels like there's something useful in the systematic exploration of these relationships.

Triangulating the information in the activity model itself.

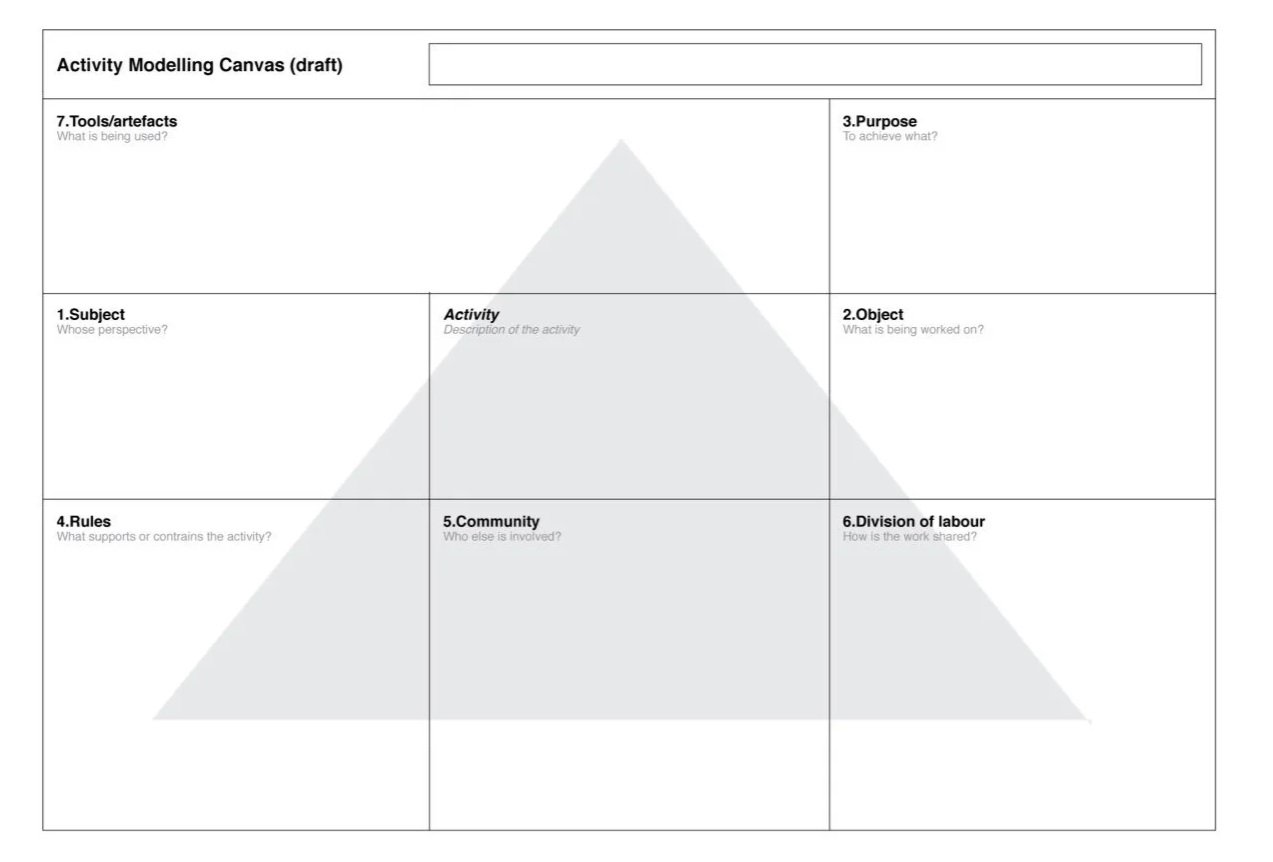

A canvas for capturing an activity system

For more immediate practical use, I've developed an activity model canvas that you can download and work with. It's designed as an aid for everyday research - a way to map what you're learning about context, spot contradictions, and frame further questions.

Because everything needs a canvas these days

A picture of connectedness

In this essay, I've tried to show how connected things resist simple explanation because they're embedded in human activity systems. The activity model doesn't resolve this complexity, but it does give us a way to investigate it - to hold the messiness steady long enough to see what's actually going on.

We can and should engage playfully with this messiness to make sense of it, whether it’s looking seriously at unserious things or just exploring serious tools to see what is possible.

I’ll leave you some words of wisdom from the most playful character of all.